Ancient Egypt

Egyptians believed that with Heka, the activation of the Ka, an aspect of the soul of both gods and humans, (and divine personification of magic), they could influence the gods and gain protection, healing and transformation. Health and wholeness of being were sacred to Heka. There is no word for religion in the ancient Egyptian language as mundane and religious world views were not distinct; thus, Heka was not a secular practice but rather a religious observance. Every aspect of life, every word, plant, animal and ritual was connected to the power and authority of the gods.

In ancient Egypt, magic consisted of four components; the primeval potency that empowered the creator-god was identified with Heka, who was accompanied by magical rituals known asSeshaw held within sacred texts called Rw. In addition Pekhret, medicinal prescriptions, were given to patients to bring relief. This magic was used in temple rituals as well as informal situations by priests. These rituals, along with medical practices, formed an integrated therapy for both physical and spiritual health. Magic was also used for protection against the angry deities, jealous ghosts, foreign demons and sorcerers who were thought to cause illness, accidents, poverty and infertility.Temple priests used wands during magical rituals.

Mesopotamia

In parts of Mesopotamian religion, magic was believed in and actively practiced. At the city of Uruk, archaeologists have excavated houses dating from the 5th and 4th centuries BC in which cuneiform clay tablets have been unearthed containing magical incantations.

Classical antiquity

Main article: Magic in the Greco-Roman world

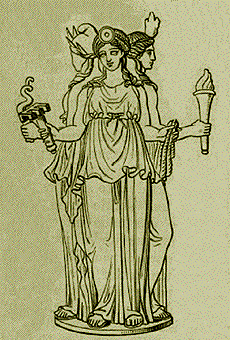

In ancient Greece magic was involved in practice of religion, medicine, and divination.

The Greek mystery religions had strongly magical components, and in Egypt, a large number of magical papyri, in Greek, Coptic, and Demotic, have been recovered. They contain early instances of:

- the use of "magic words" said to have the power to command spirits;

- the use of wands and other ritual tools;

- the use of a magic circle to defend the magician against the spirits that he is invoking or evoking; and

- the use of mysterious symbols or sigils which are thought to be useful when invoking or evoking spirits.

The practice of magic was banned in the Roman world, and the Codex Theodosianus states:

If any wizard therefore or person imbued with magical contamination who is called by custom of the people a magician...should be apprehended in my retinue, or in that of the Caesar, he shall not escape punishment and torture by the protection of his rank.

Middle Ages

Several medieval scholars were considered to be magicians in popular legend, notably Gerbert d'Aurillac and Albertus Magnus: both men were active in the scientific research of their day as well as in ecclesiastical matters, which was enough to attach to them a nimbus of the occult.

Magical practice was actively discouraged by the church, but it remained widespread in folk religion throughout the medieval period. The demonologyand angelology contained in the earliest grimoires assume a life surrounded by Christian implements and sacred rituals. The underlying theology in these works of Christian demonology encourages the magician to fortify himself with fasting, prayers, and sacraments, so that by using the holy names of God in the sacred languages, he could use divine powers to coerce demons into appearing and serving his usually lustful or avaricious magical goals.

13th century astrologers include Johannes de Sacrobosco and Guido Bonatti.

Renaissance

Further information: Renaissance magic

Renaissance humanism saw resurgence in hermeticism and Neo-Platonic varieties of ceremonial magic. The Renaissance, on the other hand, saw the rise of science, in such forms as the dethronement of the Ptolemaic theory of the universe, the distinction of astronomy from astrology, and of chemistry from alchemy.

The seven artes magicae or artes prohibitae or arts prohibited by canon law by Johannes Hartlieb in 1456 were: nigromancy (which included "black magic" and "demonology"), geomancy,hydromancy, aeromancy, pyromancy, chiromancy, and scapulimancy and their sevenfold partition emulated the artes liberales and artes mechanicae. Both bourgeoisie and nobility in the 15th and 16th century showed great fascination with these arts, which exerted an exotic charm by their ascription to Arabic, Jewish, Gypsy and Egyptian sources, and the popularity of white magicincreased. However, there was great uncertainty in distinguishing practices of superstition, occultism, and perfectly sound scholarly knowledge or pious ritual. The intellectual and spiritual tensions erupted in the Early Modern witch craze, further reinforced by the turmoil of the Protestant Reformation, especially in Germany, England, and Scotland.

Baroque

Study of the occult arts remained intellectually respectable well into the 17th century, and only gradually divided into the modern categories of natural science, occultism, and superstition. The 17th century saw the gradual rise of the "age of reason", while belief in witchcraft and sorcery, and consequently the irrational surge of Early Modern witch trials, receded, a process only completed at the end of the Baroque period circa 1730.Christian Thomasius still met opposition as he argued in his 1701 Dissertatio de crimine magiae that it was meaningless to make dealing with the devil a criminal offence, since it was impossible to really commit the crime in the first place. In Britain, the Witchcraft Act of 1735 established that people could not be punished for consorting with spirits, while would-be magicians pretending to be able to invoke spirits could still be fined as con artists.

[The] wonderful power of sympathy, which exists throughout the whole system of nature, where everything is excited to beget or love its like, and is drawn after it, as the loadstone draws iron... There is ... such natural accord and discord, that some will prosper more luxuriantly in another's company; while some, again, will droop and die away, being planted near each other. The lily and the rose rejoice by each other's side; whilst ... fruits will neither ripen nor grow in aspects that are inimical to them. In stones likewise, in minerals, ... the same sympathies and antipathies are preserved. Animated nature, in every clime, in every corner of the globe, is also pregnant with similar qualities... Thus we find that one particular bone ... in a hare's foot instantly mitigates the most excruciating tortures of the cramp; yet no other bone nor part of that animal can do the like... From what has been premised, we may readily conclude that there are two distinct species of magic; one whereof, being inherent in the occult properties of nature, is called natural magic; and the other, being obnoxious and contrary to nature, is termed infernal magic, because it is accomplished by infernal agency or compact with the devil.

Under the veil of natural magic, it hath pleased the Almighty to conceal many valuable and excellent gifts, which common people either think miraculous, or next to impossible. And yet in truth, natural magic is nothing more than the workmanship of nature, made manifest by art; for, in tillage, as nature produceth corn and herbs, so art, being nature's handmaid, prepareth and helpeth it forward... And, though these things, while they lie hid in nature, do many of them seem impossible and miraculous, yet, when they are known, and the simplicity revealed, our difficulty of apprehension ceases, and the wonder is at an end; for that only is wonderful to the beholder whereof he can conceive no cause nor reason... Many philosophers of the first eminence, as Plato, Pythagoras, Empedocles, Democritus, &c. travelled through every region of the known world for the accomplishment of this kind of knowledge; and, at their return, they publicly preached and taught it. But above all, we learn from sacred and profane history, that Solomon was the greatest proficient in this art of any either before or since his time; as he himself hath declared inEcclesiastes and the Book of Wisdom, where he saith,

- "God hath given me the true science of things, so as to know how the world was made, and the power of the elements, the beginning, and the end, and the midst of times, the change of seasons, the courses of the year, and the situation of the stars, the nature of human beings, and the quality of beasts, the power of winds, and the imaginations of the mind; the diversities of plants, the virtues of roots, and all things whatsoever, whether secret or known, manifest or invisible."

And hence it was that the magic, or followers of natural magic, were accounted wise, and the study honourable; because it consists in nothing more than the most profound and perfect part of natural philosophy, which defines the nature, causes, and effects, of things.

How far such inventions as are called charms, amulets, periapts, and the like, have any foundation in natural magic, may be worth our enquiry; because, if cures are to be effected through their medium, and that without any thing derogatory to the attributes of the Deity, or the principles of religion, I see no reason why they should be rejected with that inexorable contempt which levels the works of God with the folly and weakness of men. Not that I would encourage superstition, or become an advocate for a ferrago of absurdities; but, when the simplicity of natural things, and their effects, are rejected merely to encourage professional artifice and emolument, it is prudent for us to distinguish between the extremes of bigoted superstition and total unbelief.

It was the opinion of many eminent physicians, of the first ability and learning, that such kind of charms or periapts as consisted of certain odoriferous herbs, balsamic roots, mineral concretions, and metallic substances, might have, and most probably possessed, by means of their strong medicinal properties, the virtue of curing... though without the least surprise or admiration; because the one appears in a great measure to be the consequence of manual operation, which is perceptible and visible to the senses, whilst the other acts by an innate or occult power, which the eye cannot see, nor the mind so readily comprehend; yet, in both cases, perhaps, the effect is produced by a similar cause; and consequently all such remedies... are worthy of our regard, and ought to excite in us not only a veneration for the simple practice of the ancients in their medical experiments, but a due sense of gratitude to the wise Author of our being, who enables us, by such easy means, to remove the infirmities incident to mankind. Many reputable authors ... contend that not only such physical alligations, appensions, periapts, amulets, charms, &c. which, from their materials appear to imbibe and to diffuse the medical properties above described, ought in certain obstinate and equivocal disorders to be applied, but those likewise which from their external form and composition have no such inherent virtues to recommend them; for harm they can do none, and good they might do, either by accident or through the force of imagination. And it is asserted, with very great truth, that through the medium of hope and fear, sufficiently impressed upon the mind or imagination... Of the truth of this we have the strongest and most infallible evidence in the hiccough, which is instantaneously cured by any sudden effect of fear or surprise; ... Seeing, therefore, that such virtues lie hid in the occult properties of nature, united with the sense or imagination of man... without any compact with spirits, or dealings with the devil; we surely ought to receive them into our practice, and to adopt them as often as occasion seriously requires, although professional emolument and pecuniary advantage might in some instances be narrowed by it.— Ebenezer Sibly (1751–1800), An Illustration of the Celestial Science of Astrology, Part the Fourth.

Containing the Distinction between Astrology and the Wicked Practice of Exorcism.

with a General Display of Witchcraft, Magic, and Divination,

founded upon the Existence of Spirits Good and Bad and their Affinity with the Affairs of this World.

- "Newton was not the first of the age of reason, he was the last of the magicians." — John Maynard Keynes

No comments:

Post a Comment